SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy): Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies

Oct, 12 2025

Oct, 12 2025

Imagine waking up to a quiet bedroom and never hearing the alarm clock again. For people with epilepsy, that nightmare can become a reality through SUDEP, a sudden and unexpected death that often leaves families with more questions than answers.

Key Takeaways

- SUDEP accounts for up to 20% of deaths in people with epilepsy.

- The biggest trigger is uncontrolled seizure that occurs during sleep.

- Cardiac arrhythmia, respiratory failure, and autonomic dysfunction are the main physiological pathways.

- Effective prevention hinges on seizure control, nighttime monitoring, and addressing modifiable risk factors.

- A simple checklist can help patients, caregivers, and clinicians lower the odds of a tragic outcome.

What Is SUDEP?

Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) is a non‑traumatic, non‑cardiac death in a person with epilepsy, where the death is not due to status epilepticus, drowning, or injury. It typically occurs shortly after a seizure, often while the person is asleep, and an autopsy usually shows no clear cause.

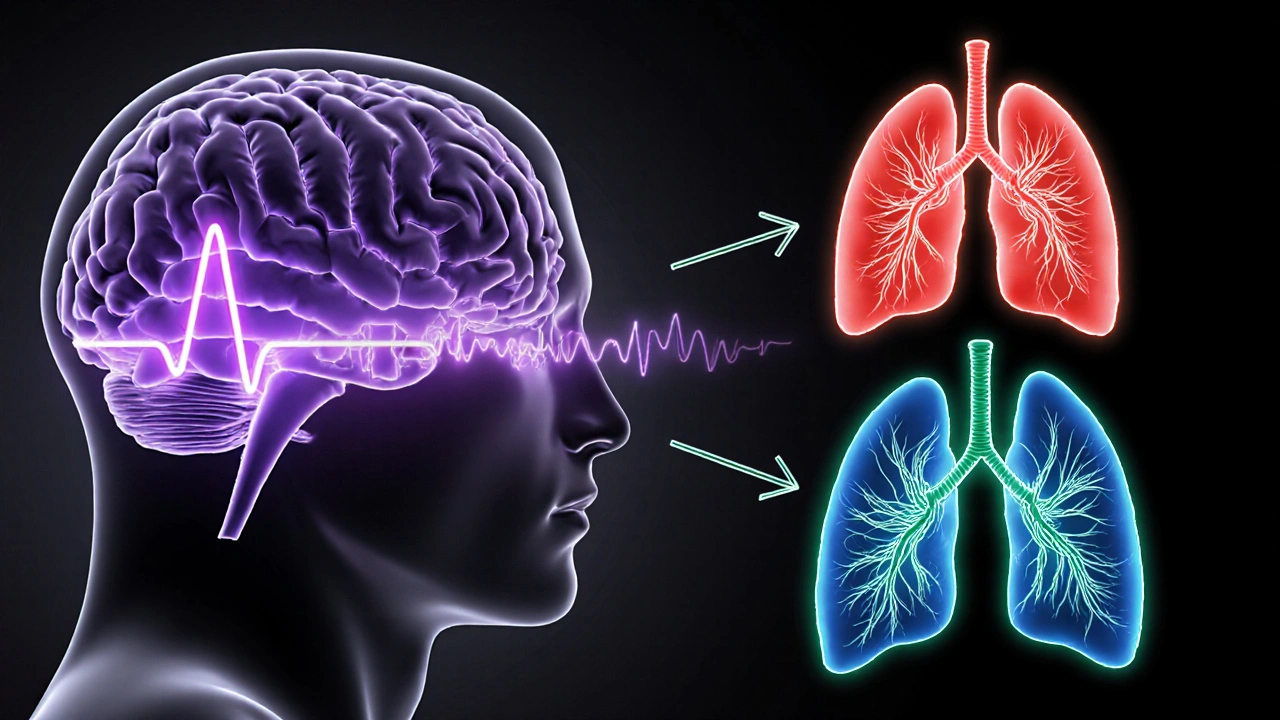

How Does SUDEP Happen?

Scientists have pieced together several pathways that can turn a seizure into a fatal event. The three most common culprits are:

- Cardiac arrhythmia - irregular heart rhythms like ventricular tachycardia can develop during a seizure, cutting off blood flow to the brain.

- Respiratory dysfunction - seizures can cause airway obstruction or apnea, leading to oxygen deprivation.

- Autonomic dysfunction - the part of the nervous system that controls heart rate and breathing may become chaotic, compounding the other two mechanisms.

These processes often overlap. For example, a seizure that blocks the airway can also trigger a surge of adrenaline, which may precipitate a dangerous heart rhythm.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Not every seizure carries the same danger. Certain risk factors raise the odds of SUDEP dramatically:

- Frequent generalized tonic‑clonic seizures (especially more than three per year).

- Seizures that happen during sleep - known as nocturnal seizures.

- Long‑standing epilepsy that began in childhood.

- Non‑adherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) or irregular medication schedules.

- Concurrent cardiac or respiratory conditions (e.g., congenital heart disease, sleep apnea).

- Use of multiple AEDs (polytherapy) that may affect heart conduction.

Age isn’t a strong predictor; both teenagers and adults can be vulnerable if these factors stack up.

Preventing SUDEP: What You Can Do Today

Prevention isn’t about a single magic bullet; it’s a blend of medical, lifestyle, and technology steps.

1. Optimize Seizure Control

Achieving the fewest seizures possible is the single most effective tactic.

- Work with a neurologist to find the right antiepileptic drug regimen. Newer agents like levetiracetam and lacosamide have fewer cardiac side‑effects.

- Consider epilepsy surgery or neurostimulation (VNS, RNS) if seizures remain uncontrolled after two medication trials.

- Track seizure frequency with a diary or an app; patterns can reveal triggers you can avoid.

2. Nighttime Monitoring

Because many SUDEP events happen while the person sleeps, having a watchful eye-even a technological one-can save lives.

- Use a seizure monitoring device that detects motion, heart rate, or oxygen saturation. Devices such as Embrace2 or NightWatch can alert caregivers via smartphone.

- If a device isn’t available, a simple bed‑partner protocol (wake up at intervals, check breathing) can be surprisingly effective.

3. Cardiac and Respiratory Screening

- Ask for a baseline ECG; some AEDs (e.g., carbamazepine) can prolong the QT interval.

- Screen for sleep apnea with a home sleep test; treating it with CPAP reduces nocturnal oxygen dips.

4. Lifestyle Tweaks

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule-sleep deprivation spikes seizure likelihood.

- Avoid alcohol and recreational drugs, which can lower seizure thresholds.

- Stay hydrated and manage stress through mindfulness or gentle exercise.

5. Education and Emergency Planning

- Teach family members how to perform position changes (recovery position) and rescue breathing.

- Keep a written seizure action plan in the bedroom and share it with caregivers.

Prevention Checklist - A Quick Reference

- ✔ Review AED regimen with neurologist every 6‑12 months.

- ✔ Log all seizures, noting time of day and triggers.

- ✔ Install a bedside seizure monitor with audible alarm.

- ✔ Schedule an ECG and sleep study if you have cardiac or respiratory symptoms.

- ✔ Follow a consistent sleep‑wake schedule (7‑9 hours for adults).

- ✔ Limit alcohol to no more than one drink per day, if at all.

- ✔ Share emergency plan with anyone who may be present at night.

Risk Factor Comparison Table

| Risk Factor | Severity | Typical Impact on SUDEP Odds |

|---|---|---|

| Frequent generalized tonic‑clonic seizures | High | Up to 10‑fold increase |

| Nocturnal seizures | High | 3‑5‑fold increase |

| Non‑adherence to AEDs | Moderate | 2‑3‑fold increase |

| Cardiac comorbidity (e.g., prolonged QT) | Moderate | 2‑fold increase |

| Sleep apnea untreated | Moderate | 1.5‑2‑fold increase |

| Age < 18 or > 60 without other risk factors | Low | Baseline risk |

Frequently Asked Questions

How common is SUDEP?

Studies estimate that 1 in 1,000 people with epilepsy die from SUDEP each year, and it accounts for roughly 15‑20% of all epilepsy‑related deaths.

Can a healthy‑looking person still be at risk?

Yes. Even if a person feels fine, frequent uncontrolled seizures or nighttime events can silently raise their SUDEP risk.

Do antiepileptic drugs increase SUDEP risk?

Most AEDs lower overall risk by reducing seizures. However, some older drugs can affect heart rhythm, so an ECG check is wise when starting or switching meds.

Is there a genetic test for SUDEP susceptibility?

Research identifies certain ion‑channel gene variants (e.g., SCN1A, KCNQ2) that may predispose individuals to fatal arrhythmias, but routine clinical testing isn’t standard yet.

What should I do if a seizure occurs at night?

If you have a monitoring device, let it alert you. If not, check breathing, roll the person onto their side, and call emergency services if breathing doesn’t resume within a minute.

Next Steps for Readers

If you or a loved one live with epilepsy, start by setting up a brief meeting with your neurologist. Bring this checklist, ask about ECG and sleep testing, and discuss whether a seizure‑monitoring device fits your budget. Remember, each small adjustment-taking medication on time, getting enough sleep, or using a bedside alarm-adds a layer of protection against that silent threat.

Sayam Masood

October 12, 2025 AT 03:52When the night grows still, hidden electrical storms in the brain can tip the delicate balance of heart and breath, turning a seizure into a silent exit. This invisible drift often catches families off guard, leaving a trail of unanswered “why”. Understanding the pathways-arrhythmia, apnea, autonomic chaos-helps us frame the mystery in a language of biology rather than fate.

Jason Montgomery

October 14, 2025 AT 11:25You've already done the hard part by learning the checklist, now keep the momentum going. Nighttime monitors are like a vigilant friend that nudges you awake before danger slips away. Stick to the medication schedule, and lean on your support crew; consistency builds the safety net that can catch a rogue seizure.

Wade Developer

October 16, 2025 AT 18:59In scholarly terms, the convergence of cardiac dysrhythmia, respiratory compromise, and autonomic instability constitutes a triad of fatal potentialities. Empirical data demonstrate that reducing generalized tonic‑clonic seizures yields a proportional decline in SUDEP incidence. Accordingly, clinicians should prioritize optimized pharmacotherapy and, where indicated, neurostimulatory interventions.

rama andika

October 19, 2025 AT 02:32Oh sure, those shiny wrist gadgets are the secret government plot to monitor every twitch you make-because nothing says "we care" like a beeping box that tells your mom when you nap. Meanwhile, the real culprits-big pharma and their “magic pills”-are probably hiding the cure in a vault, guarded by nocturnal elves.

Kenny ANTOINE-EDOUARD

October 21, 2025 AT 10:05The most effective way to lower SUDEP risk starts with tight seizure control. Every breakthrough in medication adherence translates directly into fewer nighttime episodes. First, schedule a quarterly review with your neurologist to assess whether your current AED regimen still matches your seizure profile. If breakthrough seizures persist after two adequate trials, ask about adjunctive options such as vagus nerve stimulation or responsive neurostimulation, which have demonstrated reductions in seizure frequency. Second, invest in a reliable bedside monitor that tracks motion, heart rate, or oxygen saturation; devices like Embrace2 or NightWatch can trigger an audible alarm that wakes a partner or alerts a smartphone. Third, obtain a baseline ECG, especially if you are on medications known to affect the QT interval, because early detection of conduction issues allows for timely medication adjustments. Fourth, screen for obstructive sleep apnea with a home sleep test; treating a high apnea‑hypopnea index with CPAP can smooth out nocturnal oxygen dips that otherwise increase vulnerability. Fifth, maintain a consistent sleep‑wake schedule-sleep deprivation is a well‑known seizure precipitant. Sixth, limit alcohol intake to no more than one standard drink per day, as alcohol can lower seizure threshold and impair respiration. Seventh, keep a daily seizure diary, noting time of day, triggers, and seizure type; patterns that emerge often point to modifiable lifestyle factors. Eighth, educate everyone who shares your bedroom on the recovery position and rescue breathing, so they can act within the first critical minute. Ninth, store a written seizure action plan by the bedside and review it regularly with caregivers. Tenth, consider genetic counseling if you have a family history of ion‑channel mutations, because emerging tests may identify individuals at higher cardiac risk. Lastly, remember that each small adjustment-whether it’s taking a pill on time or turning on a monitor-adds a layer of protection against that silent threat. By weaving these strategies into daily life, you turn the odds in your favor and create a safety net that can catch a seizure before it becomes fatal.

Tracy Winn

October 23, 2025 AT 17:39While the checklist is thorough, it sometimes feels like a laundry list of do‑its-take your meds, check your heart, set an alarm, log seizures, avoid alcohol, sleep enough, wear a monitor, and so on-, which can overwhelm someone already coping with daily challenges,

Jessica Wheeler

October 26, 2025 AT 01:12Choosing to ignore SUDEP is a silent betrayal of those we love.

Mikayla Blum

October 28, 2025 AT 07:45i think the key is to make the monitoring routine feel like part of your nightly chill, not a chore; a simple app reminder can keep the habit alive, and even if you sometimes forget, the data still helps your doc tweak the plan.

Jo D

October 30, 2025 AT 15:19Sure, because adding another gadget and a stack of acronyms magically fixes a complex neuro‑cardiac cascade-next they'll prescribe blockchain‑based AEDs to guarantee absolute safety.

Sinead McArdle

November 1, 2025 AT 22:52The emphasis on regular cardiac screening aligns with current best‑practice guidelines and offers a pragmatic step for many patients.

Katherine Krucker Merkle

November 4, 2025 AT 06:25It’s amazing how a tiny habit like logging every seizure can reveal hidden triggers; once you see the pattern, you can start tweaking sleep, stress, or caffeine and watch the numbers drop.

Mark Quintana

November 6, 2025 AT 13:59I’ve noticed that people who combine medication with lifestyle changes often report fewer nocturnal events, suggesting a synergistic effect worth exploring further.

Brandon Cassidy

November 8, 2025 AT 21:32Totally agree-bringing in a sleep specialist early can catch apnea before it aggravates seizure risk, and that collaborative approach saves lives.

Michelle Guatato

November 11, 2025 AT 05:05What if the pharmaceutical giants are quietly funding the research that downplays SUDEP, steering us toward pricey devices instead of affordable, widespread medication adherence programs?

Gabrielle Vézina

November 13, 2025 AT 12:39Oh, the drama, the hidden agenda-while you chase shadows, real patients beg for simple monitoring that actually works.

carl wadsworth

November 15, 2025 AT 20:12Listen up, team: we can’t afford to sit on the sidelines while evidence shows that disciplined seizure logging and nightly alarms cut SUDEP rates dramatically-take action now, schedule that ECG, and get that monitor humming.

Neeraj Agarwal

November 18, 2025 AT 03:45its important to double check the spelling of "seizure" and "monitoring" in patient notes, otherwise confusion can lead to miscommunication.

Rose K. Young

November 20, 2025 AT 11:19Honestly, anyone who brushes off the checklist as optional is playing Russian roulette with lives, and that kind of negligence is unacceptable.

Christy Pogue

November 22, 2025 AT 18:52Love how you keep the vibe upbeat, Jason-your reminder to lean on the crew really hits home, and I’m glowing with hope that together we can make the night safer for everyone.