Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: What You Need to Know About Medication-Related Emergencies

Feb, 7 2026

Feb, 7 2026

SJS/TEN Symptom Checker

Emergency Symptoms Assessment

This tool helps identify if symptoms match Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN). If you or someone you know has these symptoms, go to emergency services immediately - every hour counts.

When a simple skin rash turns into a life-threatening emergency, it’s not just a side effect - it’s a warning sign you can’t afford to ignore. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) are rare but deadly reactions to medications that start like a bad flu and spiral into skin and mucous membrane destruction. If you or someone you know develops a painful rash with blisters, peeling skin, or mouth sores after starting a new drug, go to A&E immediately. These aren’t conditions you wait out at home. They demand emergency hospital care - and every hour counts.

What Exactly Are SJS and TEN?

SJS and TEN are two ends of the same severe reaction spectrum. They’re both caused by your immune system overreacting to a medication, attacking your own skin and mucous membranes. Think of it like your body misreading a drug as an invader and launching a full-scale assault - not just on the infection, but on your skin, eyes, mouth, and throat.

The difference between SJS and TEN comes down to how much skin is damaged:

- SJS: Less than 10% of your body surface area is affected. Blisters form, skin peels off in patches, and mucous membranes (like your eyes and mouth) are deeply involved.

- TEN: More than 30% of your skin detaches. It looks like a severe burn. The skin sloughs off in large sheets, leaving raw, exposed areas vulnerable to infection.

- Overlap syndrome: 10-30% skin involvement. This is still life-threatening and treated like TEN.

It’s not just about how much skin peels off - it’s about what’s underneath. The damage goes deep: full-thickness epidermal necrosis. That means the top layer of your skin dies and separates from the layer below. This isn’t a superficial rash. It’s a systemic collapse of your skin’s protective barrier.

How Do You Know It’s Starting?

Most people don’t wake up with a full-blown SJS/TEN reaction. It creeps in. You might feel like you’re coming down with the flu: fever, sore throat, burning eyes, fatigue, and body aches. Then, within 1-3 days, a red or purplish rash appears - often starting on the face or chest. The rash isn’t itchy like an allergy. It’s painful. It spreads fast. Blisters form. Then the skin begins to peel.

Here’s what makes it unmistakable: at least two mucous membrane sites are involved. That means:

- Sores or ulcers in your mouth or throat

- Burning, red, or swollen eyes (you might feel like sand is in them)

- Sores in your genital area

If you’ve recently started a new medication - especially within the last 8 weeks - and you’re seeing this combo, don’t wait. Don’t call your GP. Don’t try antihistamines. Go straight to the emergency department. Delaying care increases your risk of death.

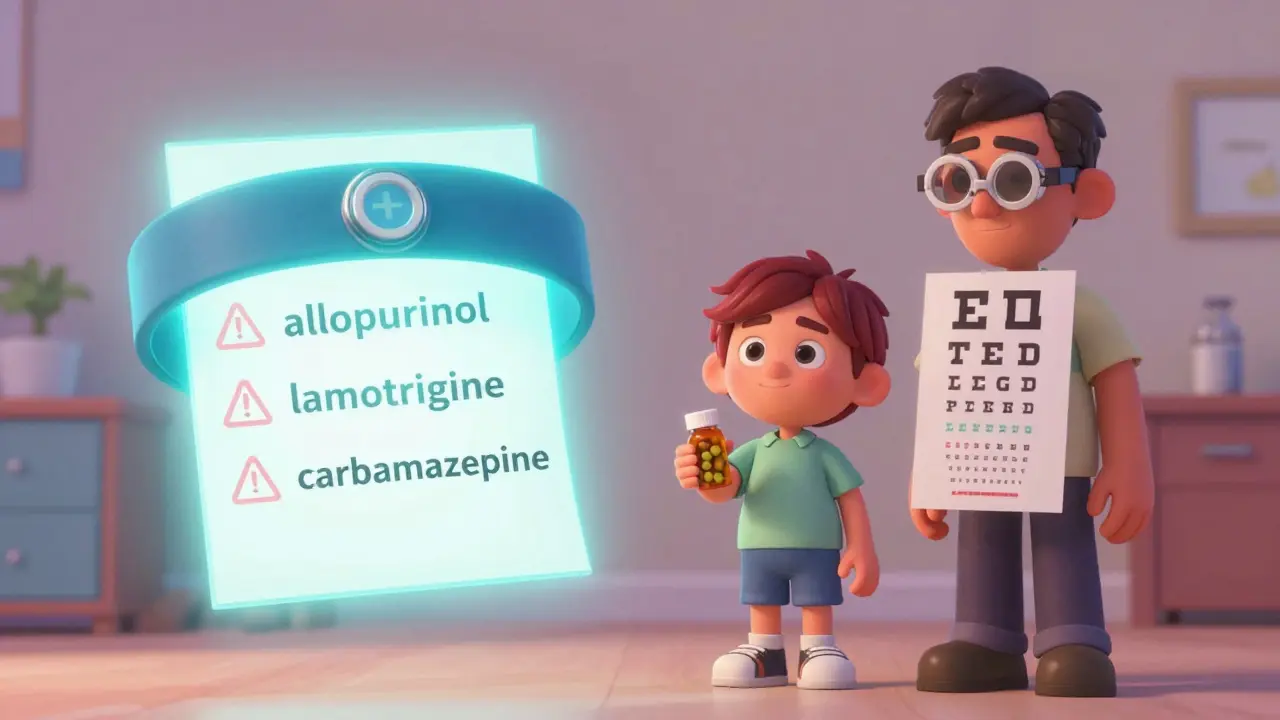

Which Medications Are the Biggest Risks?

Not all drugs carry the same risk. Some are far more likely to trigger SJS/TEN. The most common culprits are:

- Allopurinol (used for gout)

- Lamotrigine (for epilepsy and bipolar disorder)

- Carbamazepine (another epilepsy drug)

- Nevirapine (an HIV medication)

- Piroxicam and meloxicam (NSAIDs for pain and inflammation)

- Sulfamethoxazole (an antibiotic, often in combination with trimethoprim)

- Phenytoin and phenobarbital (older seizure drugs)

Here’s the scary part: if you’ve had SJS/TEN from one of these drugs, you can’t take any drug in the same chemical family again. Cross-reactivity is real. For example, if you reacted to carbamazepine, you should avoid phenytoin, lamotrigine, and phenobarbital - even if you never took them before. Your immune system remembers.

Even more concerning: some reactions happen after you’ve stopped the drug. It can take up to two weeks. So if you stopped a medication last week and now have a rash, don’t assume it’s gone. Monitor closely.

Who’s at Higher Risk?

It’s not random. Certain people are more vulnerable:

- People with HIV/AIDS - their immune systems are already altered, making reactions more likely.

- Those taking sodium valproate with lamotrigine - this combo increases SJS risk significantly.

- People who’ve had a previous rash from epilepsy drugs.

- Those allergic to trimethoprim (a common antibiotic).

- People with a family history of SJS/TEN - this suggests a genetic link, particularly with certain HLA gene variants.

- Children - though rare, SJS is more common in kids than adults.

If you’re prescribed one of these high-risk drugs, ask your doctor about your genetic risk. In some countries, testing for HLA-B*15:02 (for carbamazepine) or HLA-B*58:01 (for allopurinol) is standard before prescribing. In the UK, it’s not routine - but if you’re from Southeast Asia or have a family history, bring it up.

What Happens in the Hospital?

There’s no magic pill for SJS/TEN. Treatment is about damage control and keeping you alive. You’ll likely be admitted to a burn unit or intensive care unit - yes, the same place as severe burn victims. Why? Because your skin is no longer protecting you. You’re at high risk for infection, fluid loss, and organ failure.

Here’s what happens:

- Stop the drug - immediately. No exceptions. Even if you’re not sure which one caused it, all suspected drugs are halted.

- Fluid replacement - you lose fluids through your damaged skin. IV fluids are critical.

- Wound care - blisters are drained gently. Skin is covered with sterile dressings. No peeling off dead skin yourself - that’s done in the hospital.

- Infection control - antibiotics are given preventatively. Staff wear full protective gear.

- Supportive care - pain management, nutrition through feeding tubes (if mouth sores prevent eating), eye care with lubricants and ophthalmology teams.

Some hospitals try immunomodulators like intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or corticosteroids, but evidence is mixed. The consensus? Supportive care saves lives. No single treatment has proven to be a cure.

The Long-Term Damage

Surviving SJS/TEN doesn’t mean you’re out of the woods. Many survivors face lifelong complications:

- Eye problems - up to 50% of survivors develop chronic dry eyes, scarring, or even blindness. Regular follow-up with an ophthalmologist for at least one year is essential.

- Oral issues - mouth ulcers can lead to gum disease, tooth loss, and chronic dry mouth.

- Scarring and skin changes - dark patches, loss of pigment, or thickened scars may remain.

- Nail loss - nails may fall off and take months to regrow.

- Genital scarring - in women, vulvovaginal stenosis (narrowing) can cause pain during sex. In men, phimosis (tight foreskin) may require surgery.

- Esophageal strictures - scarring in the throat can make swallowing difficult.

One study found that 30-50% of survivors had lasting vision damage. That’s not rare - that’s the norm for severe cases. Recovery takes months. Some people need years of follow-up care.

How to Prevent It

Prevention is everything. Here’s what you can do:

- Never rush dose increases - especially with lamotrigine. The NHS warns that restarting lamotrigine after a break without slowly increasing the dose again can trigger SJS.

- Avoid new medications or foods during the first 8 weeks of starting a high-risk drug. This reduces confusion between a harmless rash and SJS.

- Know your family history - if a close relative had SJS/TEN, tell your doctor before starting any new medication.

- Check for genetic risk - if you’re of Asian descent and prescribed carbamazepine, ask about HLA-B*15:02 testing.

- Stop the drug and go to A&E at the first sign of rash + fever + mucous membrane involvement. Don’t wait for blisters.

The NHS says it best: “Stevens-Johnson syndrome is rare, and the risk of getting it is low - even if you’re taking a medicine that can cause it.” But when it happens, it’s brutal. And it’s preventable - if you act fast.

What to Do If You Think It’s Happening

Here’s your action plan:

- Stop taking the suspected drug - immediately.

- Call 999 or go to A&E - don’t wait. Say, “I think I might have Stevens-Johnson Syndrome.”

- Bring a list of all medications you’ve taken in the last 8 weeks.

- Don’t try to treat it yourself - no creams, no antihistamines, no home remedies.

- Once diagnosed, get a clear list of all drugs you must avoid forever - including similar ones.

Survivors are often given a medical alert bracelet or card. Keep it with you. It could save your life if you’re ever unconscious in an emergency.

Can Stevens-Johnson Syndrome be cured?

There’s no cure for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Treatment focuses on stopping the reaction, supporting the body while it heals, and preventing complications like infection and organ failure. Most people survive if treated quickly, but recovery can take weeks or months. Long-term damage to the eyes, skin, and mucous membranes is common and often permanent.

Is Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis the same as SJS?

TEN is the most severe form of the same condition. SJS affects less than 10% of the skin, TEN affects more than 30%. The symptoms and causes are identical - the difference is how much skin is lost. Doctors treat them the same way, but TEN has a much higher death rate - over 30% in some cases.

How long after taking a drug can SJS/TEN develop?

Most cases start within the first 8 weeks of taking the drug. But reactions can appear up to two weeks after you’ve stopped taking it. That’s why doctors warn patients to stay alert even after finishing a course of medication, especially if it’s a high-risk drug like lamotrigine or allopurinol.

Can you get SJS/TEN from over-the-counter drugs?

Yes. While most cases are linked to prescription drugs, over-the-counter NSAIDs like piroxicam and meloxicam have caused SJS/TEN. Even common painkillers can trigger it in rare cases - especially if you’ve had a previous reaction or have a genetic risk.

Do all rashes from medications mean SJS/TEN?

No. Most rashes from medications are mild and harmless. But if the rash is painful, spreads quickly, is accompanied by fever, and affects your mouth, eyes, or genitals - it’s not just a rash. It could be SJS/TEN. When in doubt, go to A&E. It’s better to be checked than to risk waiting.

If you’ve ever been told, “It’s just a rash,” remember this: not all rashes are the same. SJS and TEN are medical emergencies - not allergies, not hives, not heat rash. They’re body-wide failures triggered by drugs. And they demand immediate, life-saving action.