Nephrotic Syndrome: Understanding Heavy Proteinuria, Swelling, and Effective Treatments

Dec, 25 2025

Dec, 25 2025

When your kidneys start leaking protein into your urine, it’s not just a lab result-it’s your body sounding an alarm. Nephrotic syndrome isn’t a disease on its own. It’s what happens when the filters in your kidneys, called glomeruli, get damaged. And the signs? They’re hard to ignore: heavy proteinuria, swelling in your face, legs, or belly, and unexplained weight gain. You might notice your urine looks foamy. Your socks leave marks on your ankles. Your face feels puffy in the morning. These aren’t allergies or water retention from eating too much salt-they’re clues pointing to serious kidney trouble.

What Exactly Is Heavy Proteinuria?

Heavy proteinuria means your kidneys are spilling more than 3.5 grams of protein into your urine every day. For reference, healthy kidneys let less than 150 milligrams through. That’s a 20-fold increase. This happens because the tiny structures inside the glomeruli-podocytes and the slit diaphragms they form-get damaged. These are the gatekeepers that normally stop albumin, the main protein in your blood, from escaping. When they break down, albumin floods out. Your body tries to compensate by making more protein, but it can’t keep up. That’s when your blood albumin drops below 3.0 g/dL, a condition called hypoalbuminemia.

Low albumin doesn’t just show up on a blood test. It pulls fluid out of your bloodstream and into your tissues. That’s why you swell. The fluid collects where gravity pulls it: around your eyes in the morning, in your ankles by evening, or even in your abdomen (ascites) or lungs (pleural effusion). In kids, it often starts with puffy eyes, which parents mistake for allergies. A 2022 patient survey found nearly 80% of parents waited 7 to 10 days before seeking a proper diagnosis because of this confusion.

Why Does Swelling Happen-and Why Is It Dangerous?

Edema in nephrotic syndrome isn’t just uncomfortable. It’s a sign your body is out of balance. With low albumin, your blood doesn’t hold fluid the way it should. Your kidneys respond by holding onto sodium and water, making the swelling worse. It’s a vicious cycle. You might gain 5 to 15 pounds in days, not from fat, but from fluid. In adults, this fluid shift can lead to blood clots. The risk of renal vein thrombosis goes up 2 to 4 times when albumin drops below 2.0 g/dL. That’s not rare-it happens in 10% to 40% of severe adult cases.

Clots aren’t the only danger. You’re also more likely to get infections. Your immune proteins, like immunoglobulins, leak out with albumin. Your body’s defenses weaken. That’s why doctors check your vaccination status before starting treatment. Live vaccines like MMR or chickenpox are off-limits during steroid therapy. Even a simple cold can trigger a relapse.

What Causes Nephrotic Syndrome?

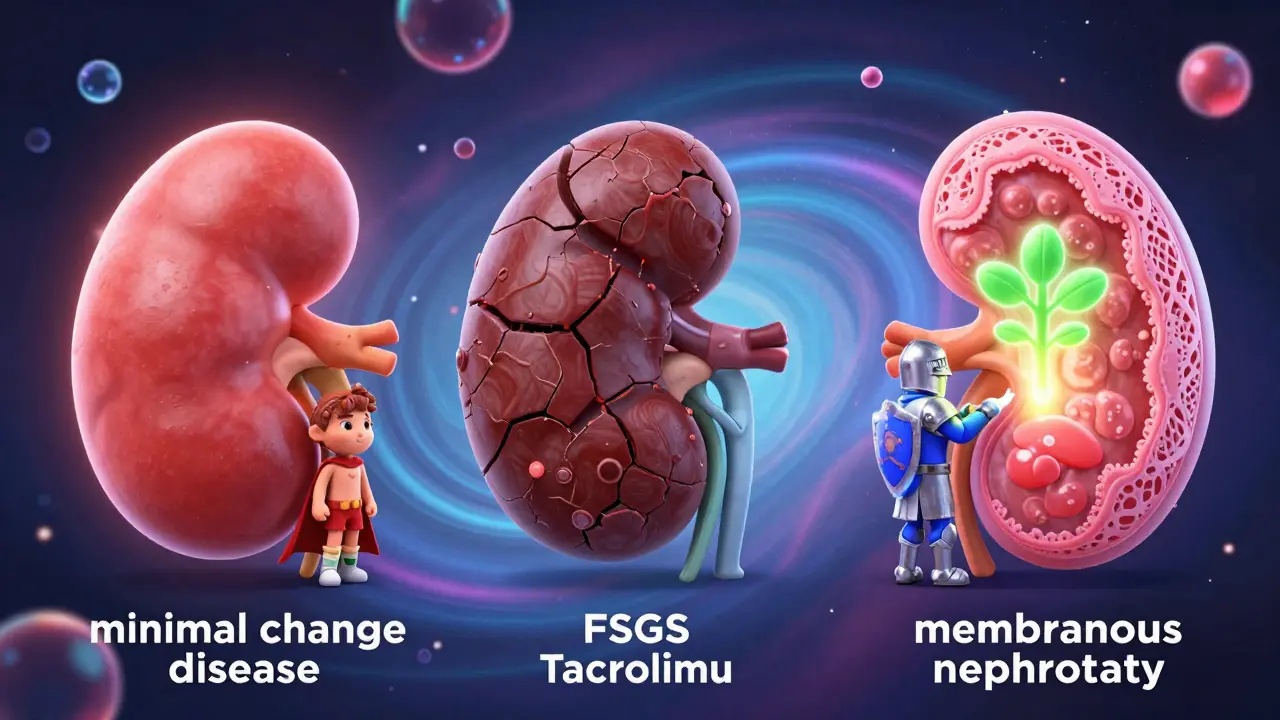

The cause depends on your age. In children under 6, it’s almost always minimal change disease-so named because under a microscope, the kidney looks normal. It responds dramatically to steroids. About 85% to 90% of kids go into remission within 4 weeks. But in adults, it’s more complex. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is the top cause, affecting 40% of adult cases. Membranous nephropathy comes next, at 30%. And then there’s diabetes, which accounts for 20% to 30% of cases in adults over 65.

Other causes include lupus, hepatitis B or C, certain medications like NSAIDs or penicillamine, and rare genetic forms. Congenital nephrotic syndrome, caused by mutations in the NPHS1 gene, shows up in babies under 3 months old with protein loss over 10 grams a day. It’s rare-less than 1% of cases-but it needs a completely different approach than steroids.

Doctors use a kidney biopsy to find out what’s causing it, especially in adults or kids who don’t respond to steroids. That’s because treatment changes based on the diagnosis. You can’t treat FSGS the same way you treat minimal change disease.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Diagnosis isn’t just about symptoms. It’s about numbers. You need three things: proteinuria over 3.5 grams per day, serum albumin under 3.0 g/dL, and swelling. Blood tests will show high cholesterol-often over 300 mg/dL. Urine tests confirm protein loss. A 24-hour urine collection is the gold standard, though dipstick tests are used for monitoring.

In kids, doctors often start treatment without a biopsy if the child is between 1 and 6 years old and has classic signs. In adults, a biopsy is almost always done. Why? Because adult-onset nephrotic syndrome is more likely to be caused by something serious-like diabetes, lupus, or FSGS-that needs targeted treatment.

Remission is defined as three consecutive days of negative or trace protein on a urine dipstick. Relapse? Three days of 2+ or 3+ protein. That’s why patients are taught to test their urine at home weekly during active disease.

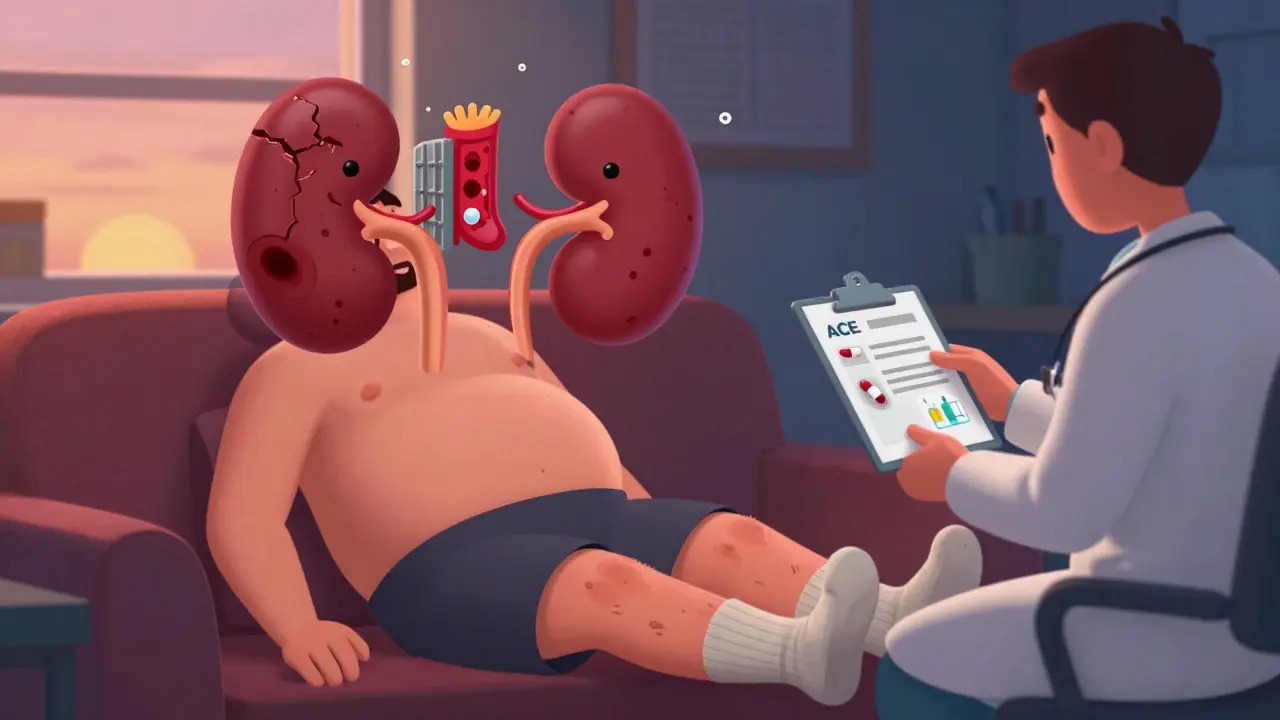

Standard Treatments: Steroids, ACE Inhibitors, and More

For children with minimal change disease, prednisone is the first step. Dose? 60 mg per square meter of body surface area, up to 80 mg a day, for 4 to 6 weeks. Then it’s slowly tapered over 2 to 5 months. Most kids respond fast. But here’s the catch: 60% to 70% will relapse at least once. Many relapse after a cold or flu.

Adults get similar steroids-1 mg per kg of body weight, up to 80 mg daily-for 8 to 16 weeks. But their response isn’t as good. Only 60% to 70% go into remission, and half of them relapse. That’s why doctors add other drugs. ACE inhibitors or ARBs are used in everyone, no matter the cause. They don’t just lower blood pressure-they reduce proteinuria by 30% to 50%. The goal? Blood pressure under 130/80 mmHg.

For steroid-resistant cases, especially in FSGS, doctors turn to calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus or cyclosporine. Rituximab, a drug used in cancer and autoimmune diseases, is now being used off-label with promising results. In some studies, it cuts proteinuria by over 50% in adults who didn’t respond to anything else.

Diet and Lifestyle: What You Can Do

Medication alone isn’t enough. Diet plays a huge role. Sodium restriction is critical. Limiting salt to under 2,000 mg a day can reduce swelling by 30% to 50% in just 72 hours. That means no processed foods, canned soups, or salty snacks. Read labels. Cook at home.

Protein intake? Don’t go low. You might think cutting protein helps, but it doesn’t. In fact, eating too little can make your body break down muscle. Stick to 0.8 to 1.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. Good sources: eggs, lean meat, tofu, dairy.

Cholesterol? It’s high because your liver overproduces lipids to make up for lost protein. Statins are often prescribed, but they’re secondary. Controlling proteinuria and sodium is more important.

What’s New in Treatment?

There’s real hope on the horizon. In 2023, the FDA approved budesonide (brand name Tarpeyo) for IgA nephropathy-but it’s showing promise in some FSGS cases too, reducing proteinuria by 31% to 59%. Another drug, sparsentan, recently completed a major trial. It’s a dual blocker of endothelin and angiotensin. In the PROTECT study, it cut proteinuria by 47.6% compared to just 14.7% with a standard blood pressure drug.

Researchers are also looking at targeted therapies. The NEPTUNE study found three distinct molecular types of FSGS. That means one day, treatment could be based on your genetic profile, not just a biopsy. Animal studies with Rho kinase inhibitors show up to 70% reduction in proteinuria. These aren’t in humans yet, but they’re coming.

Genetic testing is now recommended for kids under 1 with nephrotic syndrome or those with a family history. Why? Because if it’s congenital, steroids won’t help. You’ll need a different plan-maybe even a kidney transplant.

Long-Term Outlook: What to Expect

Prognosis depends entirely on the cause. If it’s minimal change disease, your 10-year kidney survival is 95%. FSGS? 50% to 70%. Membranous nephropathy? 60% to 80%. But if it’s from diabetes? Only 40% to 50% survive 10 years without kidney failure.

Here’s the biggest red flag: if proteinuria stays above 1 gram per day after treatment, your risk of ending up on dialysis jumps 4.2 times. That’s why doctors push so hard for complete remission. Not just partial. Not just improvement. Complete.

Relapses are common, especially in kids. But each one doesn’t mean failure. It means you need to adjust. Watch for triggers-viral infections, missed doses, stress. Keep your urine dipsticks handy. Stay in touch with your nephrologist. Most people live full lives with proper management.

Living With Nephrotic Syndrome

Parents of kids with nephrotic syndrome often talk about the side effects of steroids. Moon face. Increased appetite. Weight gain of 10% to 20%. Mood swings. Sleep problems. These are real. But they’re temporary. Most resolve once the steroid dose is lowered.

Adults report feeling isolated. The swelling makes them look different. The fatigue is crushing. Many say the foamy urine was their first clue-but they ignored it for weeks, thinking it was dehydration.

The key is early action. If you notice swelling that won’t go away, foamy urine, or unexplained weight gain, don’t wait. Get your urine and blood checked. Nephrotic syndrome is treatable. But it doesn’t fix itself.

What does heavy proteinuria mean in nephrotic syndrome?

Heavy proteinuria means your kidneys are leaking more than 3.5 grams of protein into your urine each day. This happens because the glomerular filters are damaged and can’t hold onto albumin, the main protein in your blood. It’s the hallmark sign of nephrotic syndrome and leads to low blood albumin, which causes swelling and other complications.

Is nephrotic syndrome the same as nephritic syndrome?

No. Nephrotic syndrome is defined by massive proteinuria, low blood albumin, swelling, and high cholesterol. Nephritic syndrome is different-it involves blood in the urine (hematuria), high blood pressure, reduced kidney function, and red blood cell casts in the urine. The causes and treatments are completely different.

Can children outgrow nephrotic syndrome?

Many children with minimal change disease do outgrow it, especially if they respond well to steroids. But relapses are common-up to 70% of kids have at least one. Most stop having relapses by their teens. However, if it’s caused by FSGS or a genetic condition, it’s unlikely to go away without ongoing treatment.

Why do people with nephrotic syndrome get blood clots?

When albumin drops below 2.0 g/dL, the liver makes more clotting factors, and the body loses natural anticoagulants through the urine. This creates a hypercoagulable state. The most dangerous clot is in the renal vein, which can cause sudden flank pain or kidney failure. Doctors may prescribe blood thinners if albumin is very low.

Is a kidney biopsy always necessary?

Not always in children under 6 with classic symptoms-they often respond to steroids and don’t need one. But in adults, or in children who don’t respond to steroids, a biopsy is essential. It tells you whether it’s FSGS, membranous nephropathy, or something else, and that changes treatment dramatically.

Can diet cure nephrotic syndrome?

No, diet can’t cure it, but it’s a vital part of management. Reducing sodium cuts swelling fast. Eating enough protein prevents muscle loss. Controlling cholesterol helps your heart. But medication is still required to fix the kidney damage. Diet supports treatment-it doesn’t replace it.

Amy Lesleighter (Wales)

December 26, 2025 AT 23:54Been there. Foamy urine for months thought it was dehydration. Then my ankles looked like balloons. Doc said 4.2g protein/day. Steroids made me moon-faced but it worked. Now I check my urine every week like they said. No more processed food. Life’s weird but manageable.

PS: Socks leaving marks? Yeah that’s the one.

Sophia Daniels

December 27, 2025 AT 21:54Let me tell you something real. Nephrotic syndrome isn’t some ‘oh i’ll just drink more water’ situation. This is your body screaming for help and half the people out here are still Googling ‘is foamy pee normal?’ like it’s a TikTok trend. You don’t ignore swelling that won’t go away. You don’t wait for a cold to trigger a relapse. You act. Or you end up on dialysis by 40. And no, keto won’t fix it. Stop scrolling and get tested.

Also statins? Secondary. Sodium is king. Cut the soy sauce. Cut the chips. Cook. Your kidneys will thank you.

Nikki Brown

December 28, 2025 AT 18:37People think they can ‘heal’ this with crystals or lemon water. 😒

It’s not a spiritual awakening. It’s damaged glomeruli. You need steroids. You need ACE inhibitors. You need a nephrologist who doesn’t run a wellness blog.

And if you’re one of those ‘natural remedies’ people? You’re not helping. You’re endangering kids.

Stop. Just stop.

Fabio Raphael

December 29, 2025 AT 14:09I’ve got a cousin who was diagnosed at 8 with minimal change disease. He’s 24 now, no relapses in 6 years. Steroids wrecked his mood for a bit, but he’s got a job, plays guitar, travels. It’s not the end. It’s a detour.

What helped him most? His mom learning to read urine dipstick results like a pro. And cooking every meal from scratch. No salt packets. No canned beans. Just rice, eggs, chicken, and lots of patience.

It’s hard. But it’s doable. And you’re not alone.

Steven Destiny

December 31, 2025 AT 00:07They say ‘don’t panic’ but honestly? Panic is the only thing that saves you. I waited too long. Thought my puffy face was just allergies. Turned out my albumin was 1.8. Got a blood clot in my renal vein. Spent a week in ICU. Now I’m on tacrolimus and I hate it. But I’m alive. So if you’re reading this and you’ve got swelling? Don’t wait. Don’t overthink. Go. Now.

Peter sullen

December 31, 2025 AT 11:44It is imperative to note, with a high degree of clinical precision, that the pathophysiological cascade initiated by glomerular podocyte dysfunction precipitates a hypoproteinemic state, which, in turn, triggers a compensatory hepatic upregulation of lipoprotein synthesis, thereby inducing hyperlipidemia-this is not merely a comorbidity, but a core component of the nephrotic triad. Furthermore, the sodium-retentive state induced by RAAS activation necessitates pharmacologic intervention with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, which exert both hemodynamic and antiproteinuric effects via efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction. In pediatric populations, the diagnostic algorithm must be stratified by age and steroid responsiveness; biopsy is not indicated in the classic presentation of minimal change disease in children under six years of age, per KDIGO guidelines. Adherence to a sodium-restricted diet (<2,000 mg/day) is non-negotiable. Failure to comply results in suboptimal remission rates and increased relapse frequency. Please consult your nephrologist before initiating any dietary modification.

Becky Baker

January 2, 2026 AT 11:32USA has the best treatments. Why are people still dying from this? Because they don’t trust the system. Steroids work. Kidney biopsies work. We have the science. Stop listening to influencers. Get your lab work. Get your meds. This isn’t a ‘holistic journey.’ It’s medicine. And we’re better than this.

Brittany Fuhs

January 2, 2026 AT 21:47It is profoundly concerning how casually this condition is dismissed as ‘just water retention.’ The erosion of medical literacy is not merely a societal failure-it is a moral one. To equate nephrotic syndrome with dietary indiscretion or ‘stress’ is not ignorance; it is negligence. The glomerulus is not a filter that can be ‘cleansed’ with apple cider vinegar. The loss of albumin is not a metaphor. It is a biological catastrophe. Those who trivialize this are not just uninformed-they are dangerous. I have seen children misdiagnosed for weeks because their parents believed in ‘detox teas.’ Do not be that person. Educate yourself. Or step aside.