How to Evaluate Media Reports about Medication Safety: A Practical Guide

Jan, 11 2026

Jan, 11 2026

When you read a headline like "New Study Links Blood Pressure Drug to Heart Attacks", your first reaction might be to panic-or worse, stop taking your medicine. But before you act, ask yourself: What exactly did the study actually find? Most media reports about medication safety are incomplete, misleading, or outright wrong. And the consequences aren’t just theoretical. In 2023, a Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 61% of U.S. adults changed how they took their medications based on news reports. Nearly 3 in 10 stopped taking prescribed drugs entirely. That’s not just anxiety-it’s a public health risk.

Medication Errors Aren’t the Same as Adverse Drug Reactions

One of the most common mistakes in media reporting is mixing up medication errors with adverse drug reactions. They’re not the same thing. A medication error is something that went wrong in the process-like a doctor prescribing the wrong dose, a pharmacist handing out the wrong pill, or a nurse giving the drug at the wrong time. These are preventable. An adverse drug reaction, on the other hand, is a harmful effect caused by the drug itself, even when used correctly. Some reactions are unavoidable. For example, a blood thinner might cause bleeding, even if given exactly as prescribed.A 2021 study in JAMA Network Open reviewed 127 news articles about medication safety and found that 68% never explained which type of event they were talking about. That’s a huge problem. If a report says a drug caused 500 deaths last year, is that from misuse? Or from side effects that couldn’t be prevented? You can’t tell unless the source clarifies it. The World Health Organization’s P method, a standardized tool used to assess whether an adverse event was preventable, exists for this exact reason. But you won’t see it mentioned in most headlines.

Relative Risk vs. Absolute Risk: The Hidden Trap

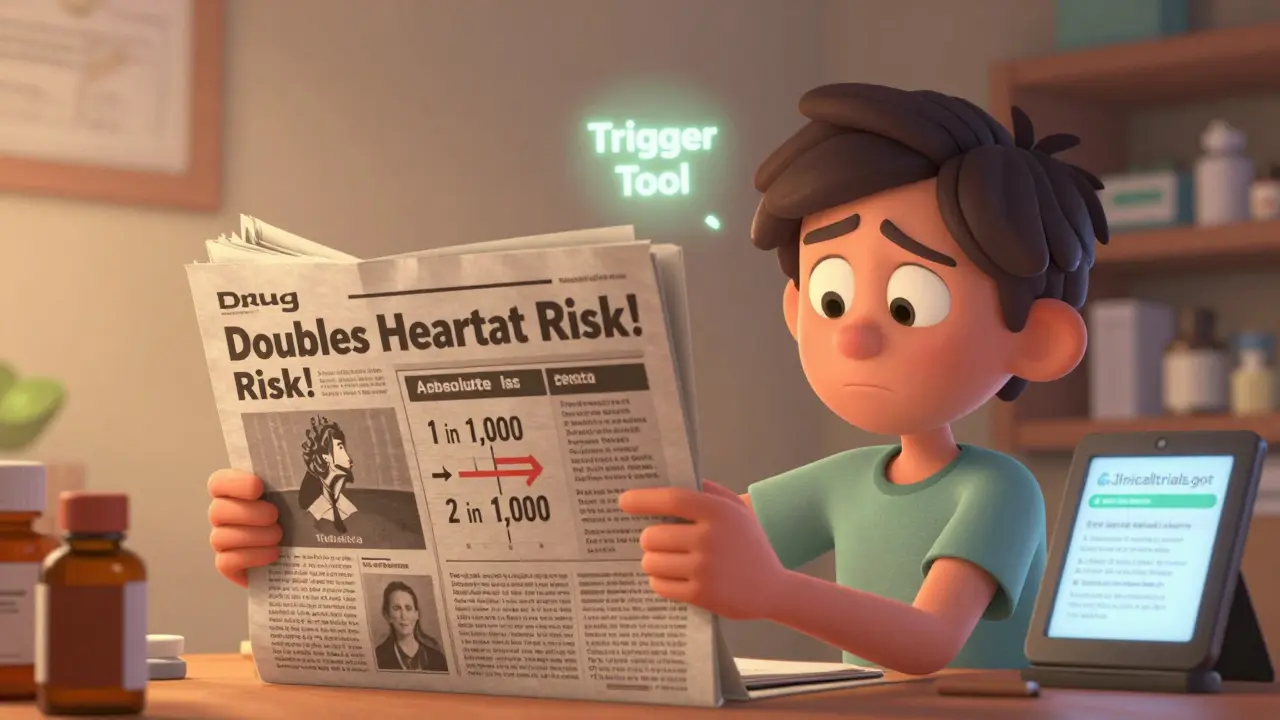

Media loves dramatic numbers. You’ll hear: "This drug doubles your risk of stroke!" That sounds terrifying. But what if your original risk was 1 in 1,000? Doubling it means 2 in 1,000. Still a tiny chance. That’s the difference between relative risk and absolute risk.A 2020 BMJ study of 347 news articles found that only 38% of reports included absolute risk numbers. Cable news outlets were the worst-only 22% got it right. Print media did better, but even then, nearly half of the stories left out the full picture. The FDA’s 2022 guidelines say you must report both. If a report only gives you relative risk, it’s incomplete. Always ask: Compared to what? And how big is the actual change?

Where Did the Data Come From? Check the Method

Not all studies are created equal. There are four main ways researchers study medication safety:- Incident report review: Hospitals and pharmacies report problems voluntarily. Easy to collect, but misses most events. Only 5-10% of errors get reported.

- Chart review: Researchers dig through medical records. More thorough, but still only catches a fraction of real incidents.

- Direct observation: Someone watches nurses and doctors in real time. The most accurate-but expensive and impractical for large studies.

- Trigger tool methodology: Uses automated flags in electronic records (like a spike in potassium levels after a new drug) to find possible problems. This is the most efficient method, according to a 2011 systematic review in PubMed. It’s used by top hospitals and the FDA’s Sentinel system.

Here’s the catch: if a media report says "A chart review found 1,200 dangerous incidents", they’re not telling you how many total patients were studied. If it was 10,000 patients, that’s 12%. If it was 1 million, that’s 0.12%. The scale matters. And most reports don’t say. Dr. David Bates, who helped develop the trigger tool, says media often overstates findings from chart reviews because they don’t mention the method’s low capture rate.

Spontaneous Reporting Isn’t Incidence Data

You’ll often see media citing the FDA’s FAERS database or the WHO’s Uppsala Monitoring Centre. These are spontaneous reporting systems. That means anyone-doctors, patients, pharmacists-can submit a report if they suspect a drug caused harm. But here’s the key: these reports are not proof of causation. They’re signals. A report might say, "Patient took Drug X, then had a seizure." But was it the drug? Or a pre-existing condition? Or something else?A 2021 study in Drug Safety found that 56% of media reports treated FAERS data as if it showed how often side effects happen. That’s wrong. Spontaneous reports are like smoke alarms-they alert you to possible danger, but they don’t tell you how big the fire is. Only controlled studies can do that. And even then, you need to know if the study controlled for other factors like age, other medications, or underlying diseases. A 2021 audit in JAMA Internal Medicine found only 35% of media-described studies did this properly.

Look for the Limitations Section (Most Don’t Have One)

Good science always says: "Here’s what we don’t know." But media reports rarely do. The same JAMA Network Open study found that 79% of medication safety articles didn’t explain the study’s limitations. That’s a red flag.Ask yourself:

- Was this a small study? (Under 1,000 patients? Results are less reliable.)

- Was it observational? (Can’t prove cause-only association.)

- Did they follow patients long enough? (Some side effects take years to show.)

- Who funded it? (Pharma-funded studies are more likely to downplay risks.)

If the article doesn’t mention any of these, it’s not trustworthy. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) guidelines say safety monitoring must include ongoing assessment-not just one study. If a report acts like one paper is the final word, it’s oversimplifying.

Check the Source: Did They Talk to Experts?

The best media reports quote experts who actually work in medication safety. Look for names like the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), the Leapfrog Group, or the FDA’s Sentinel platform. ISMP publishes an annual list of dangerous drug abbreviations (like "U" for units-people confuse it with "0" and cause errors). If a report mentions ISMP, it’s more likely to be accurate.A 2022 analysis by the National Association of Science Writers found that outlets consulting ISMP or similar resources had 43% fewer factual errors. On the flip side, outlets that didn’t consult experts were far more likely to misclassify drugs by therapeutic category. A 2022 study found 47% of reports got the drug class wrong-like calling a diabetes drug a blood pressure drug. That’s not just inaccurate-it’s dangerous.

Watch Out for Social Media and AI-Generated Content

Instagram and TikTok are the worst offenders. A 2023 analysis by the National Patient Safety Foundation found that 68% of medication safety claims on these platforms were incorrect. A viral post might say, "This statin causes dementia-stop taking it now!" But the original study? It was on mice. Or it used doses 10 times higher than humans ever take. Reddit threads like r/pharmacy are full of people calling out these lies.And now there’s AI. A 2023 Stanford study found that 65% of medication safety articles written by large language models contained serious factual errors-especially around risk numbers. If you see a news article that feels too robotic, too vague, or doesn’t cite a real study, it might be AI-generated. Always trace it back to the original source.

What Should You Do? A Simple 5-Step Check

Here’s a practical checklist you can use anytime you read a medication safety story:- Is it a medication error or an adverse reaction? If the article doesn’t say, be skeptical.

- Did they give absolute risk? If they only say "doubles risk," find the baseline number. If you can’t, it’s incomplete.

- What method was used? Was it a chart review? FAERS? A clinical trial? Look for the word "trigger tool"-that’s a good sign.

- Did they mention limitations? If not, it’s a red flag.

- Can you find the original study? Search for the journal name or DOI. Check if it’s on clinicaltrials.gov or the FDA’s website.

And if you’re unsure? Talk to your pharmacist. They see this every day. They know which drugs are commonly misreported. They know what’s actually dangerous and what’s just noise.

Final Thought: Don’t Let Fear Drive Your Health Decisions

Medication safety matters. But fear doesn’t protect you-understanding does. The global medication safety market is growing fast, and with it, the pressure to generate attention-grabbing headlines. Pharma companies, news outlets, and social media algorithms all benefit when you panic. But your health shouldn’t be a clickbait story.Stay informed. Ask questions. Demand clarity. And never stop asking: "What’s the real risk? And how do I know?" That’s the only way to cut through the noise and make smart choices about your medicine.

What’s the difference between a medication error and an adverse drug reaction?

A medication error is a preventable mistake in how a drug is prescribed, dispensed, or taken-like the wrong dose or the wrong patient. An adverse drug reaction is a harmful side effect that happens even when the drug is used correctly. Errors can be avoided; some reactions are unavoidable.

Why do media reports say a drug "doubles the risk" when it sounds scary?

They’re using relative risk, which makes small changes sound big. If your risk of a side effect is 1 in 1,000, doubling it means 2 in 1,000-still very low. Without the absolute risk, you can’t tell if the danger is real or just exaggerated. Always ask: "Compared to what?"

Can I trust data from the FDA’s FAERS database?

FAERS collects reports of possible side effects, but it doesn’t prove the drug caused them. Anyone can submit a report, and many are incomplete or inaccurate. Only about 5-10% of actual adverse events get reported. FAERS is a warning system, not a measure of how often side effects happen.

How do I know if a study is reliable?

Look for these: a large sample size (over 1,000 people), a control group, a clear description of how they controlled for other factors (like age or other meds), and mention of confidence intervals-not just p-values. If the report doesn’t explain the method or its limits, it’s not reliable.

Should I stop taking my medicine because of a news story?

Never stop a prescribed medication based on a news report alone. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist first. Many reports exaggerate risks or misrepresent the data. Stopping your medicine without guidance can be far more dangerous than the risk described in the article.

What resources should I trust for accurate medication safety info?

The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), the World Health Organization’s pharmacovigilance program, and clinicaltrials.gov are reliable sources. Hospitals that use the Leapfrog Group’s safety scores also provide transparent data. Avoid relying on social media or AI-generated content.

Next time you see a headline about a dangerous drug, pause. Check the source. Ask the hard questions. And remember: your health isn’t a headline-it’s your life.

Lawrence Jung

January 11, 2026 AT 21:17Medication safety is just another way for the system to keep us docile

They want you scared so you keep taking the pills

But nobody talks about how the real danger is the profit motive behind every drug label

Doctors get paid to prescribe

Hospitals get paid to treat the side effects

And the FDA? They’re just the PR arm of Big Pharma

Stop looking for answers in studies

Look at the money trail

That’s where the truth lives

And it’s not pretty

Alice Elanora Shepherd

January 11, 2026 AT 23:27Thank you for this thoughtful, well-researched piece-it’s exactly the kind of clarity we need in a world full of sensational headlines.

I’m a pharmacist in London, and I see patients panic over headlines like ‘doubles your stroke risk’ every week.

What they rarely realize is that if their baseline risk was 0.5%, doubling it still means a 99.5% chance they won’t have a stroke.

It’s not just about numbers-it’s about context.

Always ask: ‘Compared to what?’

And if the article doesn’t say, it’s incomplete.

Also-yes, FAERS data is not incidence data. It’s a signal, not a statistic.

And trigger tools? Absolutely the gold standard.

Thank you for mentioning ISMP too. They’re unsung heroes in patient safety.

Prachi Chauhan

January 12, 2026 AT 00:11bro i just read this article and my brain hurt

like why is everything so complicated

i just want to know if my blood pressure pill is gonna kill me

but then i read the part about absolute risk vs relative risk

and i was like ohhh

so if i had a 1 in 1000 chance before

and now its 2 in 1000

its still basically nothing

why dont they just say that

why do they say DOUBLES RISK

its manipulation

and also

stop using FAERS like its gospel

its just people typing stuff in

like if my cat sneezes after i take a pill

they put it in the database

and then the news says DRUG KILLS CATS

its madness

Katherine Carlock

January 12, 2026 AT 09:38I love this so much

I’ve been telling my mom for years not to stop her meds because of a TikTok video

She saw one saying statins cause dementia

And she was ready to quit cold turkey

I showed her the actual study

It was on mice

And the dose was like 20x what humans take

She cried

Not because she was scared

But because she realized how much she’d been manipulated

Thank you for giving us the tools to fight back

And please tell your pharmacist to keep doing what they’re doing

They’re the real MVPs

Sona Chandra

January 13, 2026 AT 15:56THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS DYING

People are too lazy to read the actual studies

They read a headline

They stop their medicine

Then they end up in the ER

And then they blame the doctors

WHY IS NO ONE HOLDING THE MEDIA ACCOUNTABLE

WHY AREN’T THEY SUED FOR MISINFORMATION

IT’S NOT JUST STUPID

IT’S CRIMINAL

AND THE FDA IS ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL

WHY AREN’T THEY PUNISHING OUTLETS THAT MISREPORT DRUG RISKS

THIS IS A PUBLIC HEALTH CRISIS

AND NO ONE IS DOING ANYTHING

Jennifer Phelps

January 13, 2026 AT 22:59so wait

if FAERS is just reports

and not actual proof

then why do news outlets keep using it like it’s a death toll

and why do people believe it

is it because it sounds more dramatic

like 500 deaths

vs

500 possible reports

that might not even be real

and how do you even find the original study

if the article doesn’t link it

is there a trick

or do you just google the drug name and hope

jordan shiyangeni

January 14, 2026 AT 20:34Let me be perfectly clear: the entire media ecosystem is complicit in this public health disaster.

Not merely negligent. Not merely irresponsible. COMPlicit.

They are not just failing to report accurately-they are actively distorting science to drive clicks, shares, and ad revenue.

And the public? The public is not a victim. The public is a participant.

You have access to PubMed. You have access to clinicaltrials.gov. You have smartphones that can search peer-reviewed journals in under three seconds.

Yet you choose to believe a viral TikTok because it confirms your fear.

That is not ignorance. That is willful stupidity.

And now you wonder why your blood pressure is uncontrolled? Why your kidneys are failing? Why your doctor refuses to refill your prescription?

Because you listened to the noise instead of the evidence.

There is no excuse.

None.

Stop blaming the system.

Start taking responsibility.

Or die.

Either way, your choice.

Abner San Diego

January 16, 2026 AT 12:29Look I get it

the system is rigged

but let’s be real

if you’re a normal person

you don’t have time to dig into every study

you got kids

you got a job

you got bills

you can’t be reading JAMA every morning

so who do you trust

your pharmacist

your doctor

or some guy on Reddit who thinks he’s a scientist

and why does it matter if the headline says ‘doubles risk’

if the drug is still killing people

even if it’s 2 in 1000

isn’t that still too many

and why are we letting pharma write the rules

why isn’t the government forcing them to show absolute risk

like it’s not that hard

just say it

don’t make us guess

Rebekah Cobbson

January 16, 2026 AT 19:04Thank you for writing this with so much care.

I’m a nurse who’s seen too many patients stop their meds after a scary headline.

One woman stopped her blood thinner because she saw a video saying it caused ‘internal bleeding’-but she didn’t know she had a 40% chance of stroke without it.

She ended up with a clot in her brain.

She survived.

But she’ll never walk the same again.

It broke my heart.

Please don’t let fear replace understanding.

Ask your pharmacist.

Ask your doctor.

They’re not perfect.

But they’re trying.

And they’re the ones who see the real numbers.

Not the headlines.

Sonal Guha

January 17, 2026 AT 07:28Stop pretending this is about information

it’s about control

the system wants you confused

so you don’t question the drugs

so you don’t ask why they cost $1000 a pill

so you don’t realize most ‘side effects’ are just side profits

the media doesn’t misreport

they report exactly what they’re paid to report

and you

you keep clicking

you keep sharing

you keep being the product

and the worst part

you think you’re being careful

but you’re just another cog